La isla del encanto, the island of bliss. What was originally a celebratory refrain has evolved into a sarcastically bitter reminder of all Puerto Rico has lost and continues to lose. While the small Caribbean island does not often make mainstream headlines, its $74 billion debt is just the start of newsworthy crisis that plagues Puerto Rico.

In attempt to rescue the island from its black hole of debt, Puerto Rico’s current governor, Alejandro García Padilla, has been meeting with a panel set up by the Obama administration about borrowing money from Washington to alleviate some of Puerto Rico’s financial troubles. Congress has allowed Padilla to lead in drafting a 10-year fiscal plan to solve the territory’s debt crisis. Padilla has a proposed a plan consisting of improving Puerto Rico’s financial reporting, combining branches of government to increase efficiency and avoid duplication, and easing regulations in order to attract investors interested in financial infrastructure and energy projects. While Padilla plans to continue decreasing government spending and collecting higher taxes, he also suggested Washington provide federal assistance through improved health programs (Walsh 2016: New York Times). Puerto Rico currently has in place a health care program called Mi Salud that covers almost half of the population. However, the program is predicted to lose federal funding within the next two years and has been delaying paying its doctors in attempt to delay its inevitable fate (Walsh 2016: New York Times). Panel members in Washington are still reviewing Padilla’s proposals, but there remains skepticism as to exactly what caused Puerto Rico’s monumental debt and how funds are being managed to make outstanding payments.

Alejandro García Padilla has been meeting with a panel set up by the Obama administration about borrowing money from Washington to alleviate some of Puerto Rico’s financial troubles. Photo (c) NY Times

However, the island’s staggering debt becomes even more perplexing after examining how it has deteriorated the island’s quality of life. The current climate is far from the paradise of piña coladas envisioned by tourists. Residents are suffering from not only increased taxes, but also fleeing doctors, inadequate housing and schools, and lack of general resources.

It is estimated that Puerto Rico loses a doctor everyday. Waiting rooms have evolved into a sort of agonizing purgatory as the demand of patients outweighs the supply of doctors. Patients die while waiting to be seen by a physician. To see a dermatologist or a rheumatologist, Puerto Ricans are facing an average five-month wait (Block 2016: NPR). As of now, it seems like this wait period is likely to increase rather than decrease as current doctors in training cannot afford to stay on the island after completing their residency due to lack of pay in Puerto Rico and job offers calling from the mainland.

This exodus of doctors highlights another major problem Puerto Rico has been battling, its brain drain due to lack of viable job or career opportunities for even its most educated residents. It seems as if disease has spread beyond the health of its people to the quality of education offered in the island. Over 150 schools have been closed island wide due to cuts in educational budgets (Guadalupe 2016: NBC News). Even the few who have the opportunity to earn a quality education are forced to leave because there is no opportunity for social mobility or reliable career paths in their home of Puerto Rico. In the past decade of economic downfall, Puerto Rico has experienced the largest migration of its residents to the mainland since WWII. This creates a paradox in which other countries benefit from the original investment Puerto Rico made in its peoples’ education as they spend the most productive years of their lives anywhere except their home. Without reliable professionals the territory has no chance of sustaining itself.

Photo (c) Primera Plan Nueva York 2016

The few jobs that are available to natives on the island are a joke in terms of pay. Most families live in federal housing and fall below the poverty level even while being employed fulltime. Average incomes in Puerto Rico are only one third the average in the United States, making it no surprise that the island has America’s second-largest public housing system (Walsh 2016: New York Times). Those who live in public housing in Puerto Rico either have a reported income or do not. For those who earn an income, their rent and utilities can amount to no more than 30% of their adjusted income according to federal policy. However, the Federal Housing and Urban Development reported that 36% of Puerto Ricans living in public housing earn no income, but they still have to pay a minimum of $25 a month. This minimum payment essentially converts to “negative rent” after utilities are factored in (Walsh 2016: New York Times). For islanders who manage to afford housing on their own, real estate values were reported to have dropped at least 40% in 2014 (Gutierrez 2014: The Washington Examiner). Such conditions are unimaginable but have somehow morphed to the norm in Puerto Rico. The island is drowning in its debt to such an extent that basic needs such as shelter and food cannot be adequately provided to its people.

As if it was not already struggling enough, Puerto Rico recently experienced major power outages in September of this year. While power outages are a fairly common occurrence, this one may have been the darkest to strike the island yet. About 1.5 million people lost power, a third of the island’s total population. The outage caused major traffic congestion and forced already suffering businesses to close early and lose earnings. Light finally started to illuminate the island again, but what seemed like hope was a false mirage. The light came from fires that spread ramped across the Puerto Rico worsening its already gruesome state, some from the power outage others from faulty generators (BBC News: 2016). All of this chaos was to blame once again on Puerto Rico’s looming debt. The Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority has been in desperate need of updated equipment, as most of it is outdated and malfunctioning. However, it seems hardly coincidence that officials were never able to determine the exact cause of the fire while the Power Authority is responsible for $9 billion of Puerto Rico’s $74 billion debt, over 10% of the island’s total financial blackout.

The present day circumstances of economic despair in Puerto Rico can be compared to Kwame Ture and Charles V. Hamilton’s theory of Internal Colonialism. While Puerto Rico is not within the contiguous borders of the United States, it is still considered an American territory, and therefore, part of the country. But if Puerto Rico is part of the United States, how is it possible that it has been allowed to reach such rock bottom? The current unfathomable reality of Puerto Rico’s paralyzing debt, lack of jobs, and nonexistent resources can be compared to urban ghettos within the States. The idea of traditional colonialism is associated with a powerful country dominating another abroad, leaving the less powerful country victim to exploitation and oppression. The lens of Internal Colonialism redirects this attention to focus on how dominant groups achieve the same patterns of exploitation by preying on weaker groups in their own backyard. As Ture and Hamiltion (1992) explain, “the social effects of colonialism are to degrade and dehumanize” (Ture and Hamilton 1992: 31), which can occur anywhere regardless of location.

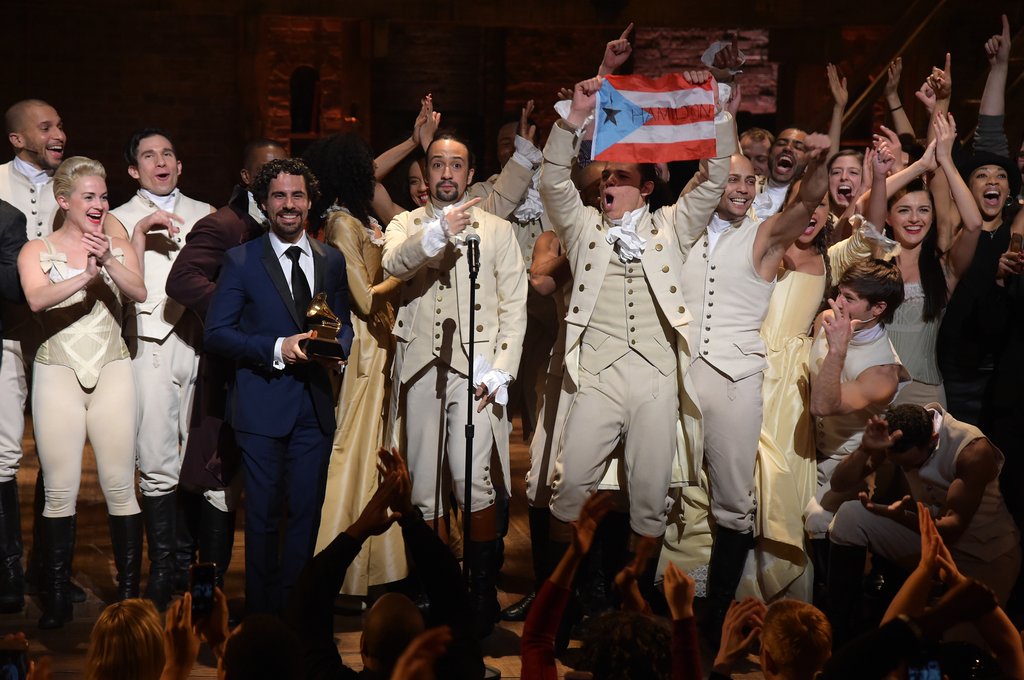

Even Hamilton’s musical director and writer, Lin-Manuel Miranda, has responded to the apprehension of Washington stepping in, “It’s not a bail out. What we’re asking is the right to restructure this debt and get relief”. Photo (c) Pop Sugar 2016

While Ture and Hamilton focus on the Black Power movement and historic trends across the African American community, these patterns of oppression caused by hegemonic standards are mirrored in Puerto Rico. Such trends are why Washington allowed Padilla to lead in devising a restoration plan for Puerto Rico’s debt crisis rather than having to deal with the backlash of having an American authority in charge. It is not ideal that Padilla had to even approach Congress, but if Washington does not assist in bailing the island out Padilla predicts they will accumulate up to an additional $59 billion in debt over the next 10 years. Puerto Rico had no choice but to beg for mercy due its own desperation and lack of political or financial resources.

Nonetheless, allowing Padilla to lead in what was merely brainstorming is hardly a compromise. There is a vast possibility of other options that could aid Puerto Rico and allow it to restructure its debt including drafting a path to statehood, having federal tax dollars to contribute toward paying off Puerto Rico’s debt, or allowing Puerto Rico to file for Chapter 9 bankruptcy. Cities in the States such as New York and Detroit have both had the option of declaring bankruptcy under Chapter 9 in order to confront an insurmountable amount of debt (White 2016: The Atlantic). But along with so generously throwing Padilla a bone, Congress has drafted and introduced a bill known as Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act, better known as PROMESA. If passed, PROMESA will provide Puerto Rico with a board of seven members from Washington to “oversee the development of budgets and fiscal plans for Puerto Rico’s instrumentalities and government. The board may issue subpoenas, certify voluntary agreements between creditors and debtors, seek judicial enforcement of its authority, impose penalties, and enforce territorial laws prohibiting public sector employees from participating in strikes or lockouts” (Library of Congress: H.R. 4900). While Puerto Rico needs help from Congress, this bill is not the answer most Borricuas were hoping for. The concern surrounding PROMESA is that it forfeits Puerto Rico’s autonomy and agency to fix its own problems. The bill has so far caused hostility and debate from several perspectives. Congress members who have voted in favor of the bill have done so shrugging their shoulders – not really agreeing with what it offers but not knowing what else to do. Senator Bob Mendez has voiced much criticism against the bill saying, “PROMESA exacts a price far too high for relief that is far too uncertain” (Gamboa 2016: NBC News). The sentiment expressed by Mendez is one shared by many Puerto Ricans. They fear that should this bill pass, the little they have left in terms of their roots, culture, and identity will be disappear along with the billions of dollars that have evaporated from the island’s shores. Even Hamilton’s musical director and writer, Lin-Manuel Miranda, has responded to the apprehension of Washington stepping in, “It’s not a bail out. What we’re asking is the right to restructure this debt and get relief” (Guadalupe 2016: NBC News). Whether or not PROMESA is the relief Puerto Rico needs is still uncertain.

An empty PROMESA? Photo (c) The Economist 2013

While there are many ways to approach this ordeal at hand, maybe Puerto Rico should consider a process of political modernization similar to what Ture and Hamilton suggested for the Black community in America. The situation in Puerto Rico validates how underrepresented minority groups in the United States, whether on the mainland or on a territory, lack agency to advocate for themselves. Ture and Hamilton characterize political modernization by three major concepts, “(1) questioning old values and institutions of the society; (2) searching for new and different forms of political structure to solve political and economic problems; and (3) broadening the base of political participation to include more people in the decision-making process” (Ture and Hamiltion 1992: 39). With upcoming governor elections and Congress voting on whether or not to pass the PROMESA bill, Puerto Rico needs to be aggressive in deciding what is to take place next. Instead of settling for what is likely to be an inadequate solution to a pressing issue from Washington, Puerto Rico should adopt the Black Power mentality of political modernization in order to change the course of its fate. Should PROMESA pass, whoever is elected governor will have to work with the board to make decisions for Puerto Rico. This hybrid of political structure will definitely be a “new and different” from past forms the island has experienced. But if Puerto Ricans fail to maintain an invested interest by challenging and questioning whether political officials are taking steps in Puerto Rico’s best interest, then Borricuas will be unable to complain about their problems if they take a sideline seat. In the past four governor elections in Puerto Rico (2000, 2004, 2008, 2012) the winning party has won only by about 3%; the margin of victory for the past two out the last three elections has been less than 0.5% (Luis Dávila Colón 2016: Univision Radio). Such a close call suggests there is room for more Puerto Ricans to take a stand and use their voice to save what is left of their island.

Puerto Rico, once known as la isla del encanto is now more often compared to Gabriel García Marquez’s Macondo due to its rapid deterioration. The fictional town and Puerto Rico share in common lack of institutional infrastructure and inevitable invasion from outsiders. Only time will tell whether or not Puerto Rico will find a way to save itself or disappear into the abyss like the small town in One Hundred Years of Solitude.

References:

Colón, Luis Dávila. (2016). “Macondo vive aquí.” New York, NY: Univision Communications Inc.

“Puerto Rico: Huge blackout after plant fire.” (2016) BBC News: US & Canada. Copyright 2016 BBC.

Ture, Kwame and Charles V. Hamilton. (1992). Black Power: The Politics of Liberation. New York, NY: Random House, Inc.

Walsh, Mary Williams. (2016). “A Surreal Life on the Precipice in Puerto Rico.” New York, NY: The New York Times Company.

Walsh, Mary Williams. (2016). “Puerto Rico’s Governor Warns of Fiscal ‘Death Spiral.’” New York, NY: The New York Times Company.